China's Plan to Establish a Permanent Base on the Moon - バイリンガル字幕

The United States and its partners are currently preparing the next steps of the Artemis program,

including crew lunar missions and the construction of the gateway.

On the other side of the Pacific,

China is also preparing its own competing lunar base plans, called the ILRS, or International Lunar Research Station, and scheduled for the 2030s.

Both nations have one objective in mind, establishing long-term presence on the Moon.

So in this video,

we're going to review where the Chinese are at,

what exactly is the ILRS, and if China can overcome the obstacles to make its lunar outpost truly international.

This video is sponsored by Private Internet Access.

More on them later.

It's October 15, 2003.

China is feeling confident.

After 10 years of development, its human spaceflight program just succeeded in putting its first astronaut into orbit, becoming the third country to do so.

A year later, in January 2004, China decides to expand its ambitions beyond the Earth's orbit.

It officially inaugurates the CLEP, the Chinese Lunar Exploration Program.

This interest for the Moon is not limited to China.

The world was regaining its interest for our planet's only natural satellite,

and the following years,

historical space powers like the US, Russia, and Europe, alongside new entrants like India and Japan, would sketch out their own lunar planets.

And in this competitive context, China's CLEP program becomes a pro.

The moon is seen as the closest planetary body to Earth, and the ideal stepping stone for deep space exploration.

It's also a goal for space sciences, and success on the moon would mean incomparable benefits for China in terms of soft power.

And some prominent Chinese space officials are also pushing the idea of commercial lunar applications.

So, over the next 20 years between 2004 and 2024, China would carry out 6 lunar missions

named Chang'e 1-6, each of them carrying out tasks with progressive difficulty.

The first two missions orbited the moon, studying the surface and mapping its topography, and this is Chang'e 1-2.

2.

The Chinese would then move on to soft landing landers and rovers with the Chang'a 3 and 4.

And more recently,

two lunar sample return missions,

the Chang'a 5 and 6, have brought back samples to the Earth with the latest mission launching as recently as May 2024.

And so, emboldened by these successes, China today is moving to the next big step, the the International Lunar Research Station.

The first mention of the ILRS by high-level Chinese officials dates back to 2016.

At the time,

the ILRS concept seemed to echo the European Moon Village, which was another multilateral lunar base concept proposed by the European Space Agency in 2015.

as a matter of fact, Europe and China as well as Russia were reported at the time to be discussing joint lunar plans.

It's also around this period in 2017 that the US announces the Artemis program,

outlining America's ambitions to return humans to the Moon 50 years after Apollo.

But before we get into how all of this unfolds,

I would like to briefly pause and mention our sponsor for today's video, Private Internet Access.

Private Internet Access is a VPN, a fantastic tool if like me, you're concerned about safety issues when using the internet.

What a VPN software does is that it masks your device's IP address,

encrypting it and routing it through secure networks, hiding your online identity and This is typically very useful if you use public Wi-Fi networks.

With a VPN, you can also choose the country of the server you're routing your data through.

And this is helpful for example when you're doing online research,

as some websites will block you based on the country of origin of your IP, and I've definitely experienced this while doing China's space.

By cleverly selecting your VPN service country,

you can also get access to better deals when shopping online, buying airline tickets, as well as viewing region-restricted content on platforms like Netflix.

For example,

for one of my favorite movies,

Interstellar, you can see that it is not available in the US or in France, but by switching my country to Canada on my VPN, Interstellar

unlocked.

Private Internet Access VPN brings all of these benefits in an easy-to-use app available for smartphones,

tablets, and laptops, and currently running a massive 83% discount where you can get a two-year subscription for $2.03 a month, as well as an additional four

months for free, and this subscription is available for an unlimited number of devices.

And if you're ever unsatisfied, be also included.

money back guarantee.

So miss out on this incredible offer.

Get your subscription now at pivpn.com slash dulphong hour.

Thank you private internet access for sponsoring this video.

And with that, back to China's lunar program.

So it's the late 2010s.

China has presented the ILRS moon-based concept, and many discussions with other space-faring nations are taking place behind closed doors.

The big milestone occurs in June 2021.

ILRS is officially announced.

It's no longer just a concept.

It's an actual project, and specifically, it's now a Sino-Russian joint project.

The announcement, is now alongside the signature of an MOU between the Chinese and the Russians, presenting the ILRS as an international endeavor.

Although considering the smaller Russian budget and their recent lunar track record, Russia will probably play the role of the junior partner here.

But more significantly, documents are published to describe what the ILARIS would look like.

Three phases have been envisioned.

Phase consists in developing the preliminary model of the station, also known as Jibenshinu.

This phase extends from basically now all the way to 2030.

During these six years,

China plans to undertake three missions, the Chang'e Six, which launched in May 2024 to collect samples from the far side of the moon.

And then there's Chang'e Seven and Chang'e Eight, respectively in 2026 and 2026.

These are individual missions.

They aim at building a lunar base per se,

but they aim at testing core technologies that would enable a permanent Chinese presence on the lunar surface.

This includes learning to land at the lunar South Pole,

experimenting with inter-lunar spacecraft communications,

deploying a series of lunar relay satellites, validating the presence of ice at the South Pole, and experimenting with in situ resources utilization.

However, the deal starts during Phase II of the ILS, also known as the construction phase, and scheduled between 2030 and 2040.

Five missions have tentatively been defined, and while these may shift a little bit in the future, today this is what we need.

One of the main missions,

sometimes called the ILAR-1,

will aim at the establishment of a lunar command center,

including basic energy and telecommunication facilities to power lunar infrastructure and enable autonomous spacecraft Now,

a couple of tangible examples of what this could be, and is my speculation.

But in May 2024,

the Director-General of Rose Kosmos,

Yuri Borisov, mentioned that Russia was in talks with China to co-develop nuclear power plants on the lunar surface around 2033-2035.

Navigation services and communications for China's lunar base will also be necessary,

and China unveiled last year a plant to deploy a lunar constellation called Tretchao.

seen satellites in various lunar orbits in the 2030s.

Another crucial aspect of a permanent lunar presence will be the utilization of in situ resources.

And this is at the core of another mission, sometimes referred to as the ILARS-3.

The ice at the south pole naturally comes to mind, with idea of extracting liquid water, hydrogen, and oxygen.

Lunar will also be a major focus, as oxygen in various metals can be extracted from the metal oxides it contains.

Regolith can also be used for building material,

either by forming bricks or with 3D printing techniques, and know that several Chinese universities have already been experimenting with this using lunar regolith simulates.

The remaining three ILRS missions will primarily focus on space science.

One of them will aim at establishing the facilities related to, quote unquote, lunar exploration and research.

And so this will be things like sampling infrastructure and the associated instruments to analyze the samples.

There's also the capture of lunar particles and further investigation of lunar geology using ground penetrating.

We also know that China is interested in exploring lunar lava tubes, which are seen as potential locations for future human establishments.

China is also bullish on lunar-based astronomy,

as the lunar south pole and the far side of the moon have this unique advantage of being shielded from human electromagnetic activity,

and it's understood that the ILRS will actually have an entire mission dedicated to this cause.

Finally, China will also explore bioregenerative systems, which essential to sustained life in a closed-loop environment.

This is something that China has already dabbled with a little bit,

with the Chang'e 4 mission carrying a small biosphere experiment in 2019,

and also the Wegong experiments in Beijing,

which simulated a closed moon base which tested systems to recycle water, regenerate oxygen, and grow a majority of the food in turn.

Now, to launch all of this space hardware, China plans to develop two super heavy lift rockets.

There is the Long March 10, currently already in development, and scheduled to perform its maiden launch in 2027.

Similar in payload capacity to the Falcon 9, it be capable of sending 27 tons into a trajectory towards the moon.

This rocket will be followed in 2033 by the much heavier Long March 9,

a Starship-class launch vehicle which will be partially reusable and capable of of payload to the moon.

That's six times the capacity of China's current largest rockets, the Long March 5.

These new rockets will also enable a human presence on the moon,

because the Long March 10 will be human-rated and will be able to carry the Chinese equivalent of the Orion spacecraft called Mengzhou,

as well as a twin.

26-ton crude lunar lander, called Lan Yue.

Both of these spacecraft are currently under development,

and China is aiming to land its first astronauts on the moon in 2030,

and this could open the gate to regular short-term visits to the Ilaras from Chinese and potentially foreign astronauts.

Now question, can this Ilaras lunar base become international, similar to the NASA-led Artemis program?

China certainly hopes so, and often described the Ilaras as, quote-unquote, proposed by China but jointly built with other countries.

In 2023,

China announced the ILRS Cooperation Organization,

aka the CO,

which will be headquartered in the Chinese city of Hafe, and aims at including all the countries which want to participate in the ILRS.

China's timeline was to issue invitations to countries globally in 2023, followed by MOUs and formal intergovernmental agreements by the end of 2024.

Up to now, a small dozen countries have joined the ILRS, but recruiting members for China has been challenging.

And this is especially apparent when you compare to the list of countries that have signed the Artemis Accords.

One notable aspect is the absence of any Western country in the ILRS, which may seem a little bit unexpected.

I mean,

the US's non-participation is unsurprising,

but European countries,

on the other hand,

have this long tradition of cooperating with China in space,

including on the recent Chang'e 6 mission which carried instruments from France, ESA, and Italy.

But as we dig deeper into the of members, there's Russia, as well as close allies of Russia, which Belarus, Azerbaijan, Serbia, Venezuela, and Nicaragua.

Following the invasion of Ukraine in 2022, collaborations in space between Europe and Russia have come to a standstill.

And so,

due to the presence of Russia and its allies in the IRS, it now seems really unlikely for any European space power to join.

And China seems to be aware of this, because they tend to erase Russia from their presentations destined to an international audience.

Now, beyond Western countries, there are many so-called non-aligned countries interested in the moon.

This is the case of Brazil,

Saudi Arabia,

or UAE,

which are known to be keen on cooperating in space with China,

but a lot of these countries have already signed the Artemis Accords,

and in the case of the UAE, have signed bilateral agreements with NASA to be part of the Artemis program.

And so it really remains to be seen if countries can be part of both Artemis and the ILR.

China's ILARS cooperation goals are sometimes called the 555, which signing on 50 countries, 500 international scientific institutions, and 5,000 researchers.

And this may be challenging,

because I mean, there aren't even 50 countries that have signed the Artemis Accords, let alone bilateral agreements for the Artemis program.

And I think beyond quantity,

it's also a Aside from Russia and perhaps Turkey and South Africa,

other ILRs members all have a very small space budget and sometimes have an in-existent space program.

Compare this,

for example, to the space budgets of the top 10 countries having signed the Artemis Accords, and you realize that the gap is massive.

This means that many members of the ILRS will likely have a limited role.

Now, another fascinating aspect to watch is whether China will be willing to delegate

the construction of critical ILRS modules to partner with I mean,

in the past,

China has been eager to invite international partners on its missions, but under the form of providing an instrument or a piggyback payload.

If we took the Arnus program in comparison,

NASA has entrusted the Europeans to build this service module for the Orion spacecraft, which will provide propulsion, power, and life support systems.

ESA and JAXA are building the Lunar Gateway habitation Canada is building the very important Canadarm3,

and the UAE will provide the airlock module of the gateway.

I think that this kind of mindset shift, if it takes place for the IRS, would truly signify that it is becoming an international program.

In any case,

both the ILRS and the Artemis program are going to be fascinating endeavors, and doubly, the most ambitious space programs ever launched by mankind.

So let's keep our eyes peeled,

and to stay informed on the progress of the Chinese side,

make sure you subscribe to don't forget As always,

a special thank you to my patrons on patreon.com and YouTube memberships for supporting my work.

The recent months haven't been easy for me,

a lot has been going on,

and I haven't been able to make as many videos as I hoped, so thank you Patrons for your continued support.

With that, thanks for watching, and I'll see you in the next video.

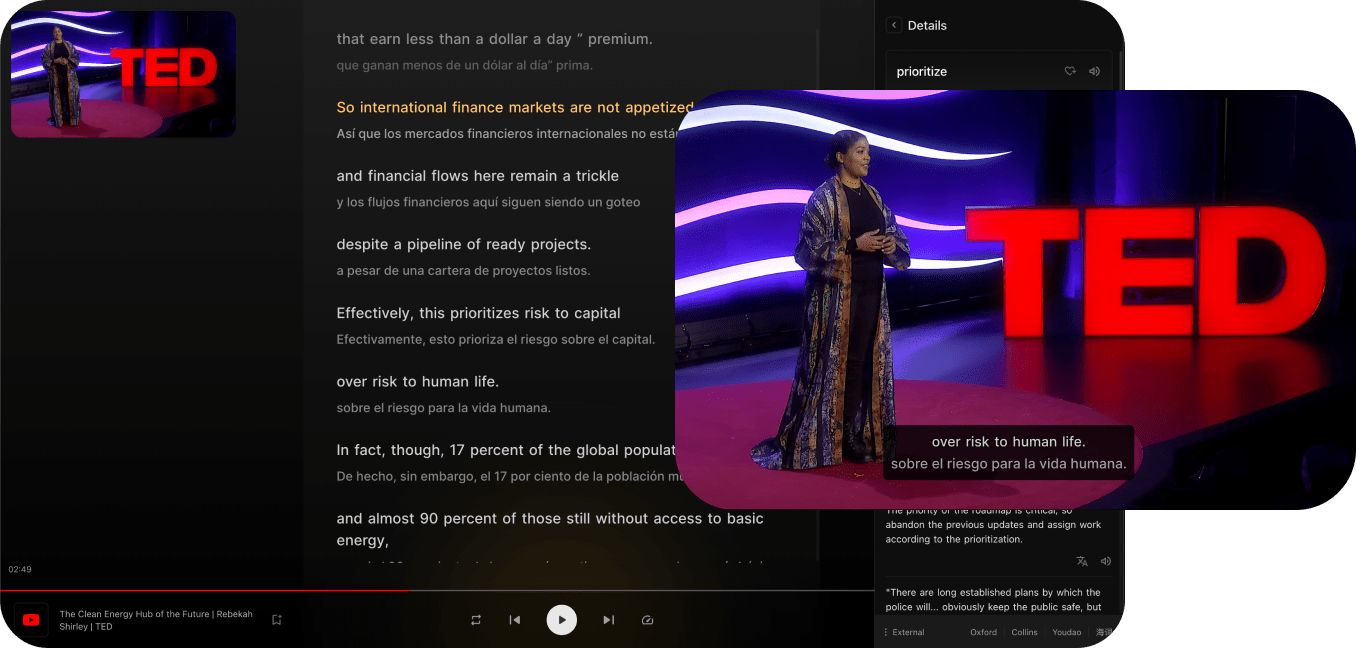

さらなる機能をアンロック

Trancy拡張機能をインストールすると、AI字幕、AI単語定義、AI文法分析、AIスピーチなど、さらなる機能をアンロックできます。

主要なビデオプラットフォームに対応

TrancyはYouTube、Netflix、Udemy、Disney+、TED、edX、Kehan、Courseraなどのプラットフォームにバイリンガル字幕を提供するだけでなく、一般のウェブページでのAIワード/フレーズ翻訳、全文翻訳などの機能も提供します。

全プラットフォームのブラウザに対応

TrancyはiOS Safariブラウザ拡張機能を含む、全プラットフォームで使用できます。

複数の視聴モード

シアターモード、リーディングモード、ミックスモードなど、複数の視聴モードをサポートし、バイリンガル体験を提供します。

複数の練習モード

文のリスニング、スピーキングテスト、選択肢補完、書き取りなど、複数の練習方法をサポートします。

AIビデオサマリー

OpenAIを使用してビデオを要約し、キーポイントを把握します。

AI字幕

たった3〜5分でYouTubeのAI字幕を生成し、正確かつ迅速に提供します。

AI単語定義

字幕内の単語をタップするだけで定義を検索し、AIによる定義を利用できます。

AI文法分析

文を文法的に分析し、文の意味を迅速に理解し、難しい文法をマスターします。

その他のウェブ機能

Trancyはビデオのバイリンガル字幕だけでなく、ウェブページの単語翻訳や全文翻訳などの機能も提供します。