A 2024 Cardiovascular Prevention Update | Michael Miedema, MD, MPH; & Felipe Martignoni, MD, PhD - 双语字幕

Excellent.

So thank you for This is kind of our prevention grand rounds for the year.

It's going to myself and Dr.

Martin who's our prevention fellow presenting this morning.

So I'm going to 20 minutes or so on a lipid update and then he's going to spend about

20 minutes on his work he's been doing in Lipoprotein A here at the foundation.

and just kind of in the broader context of how we should be using lipoprotein A clinically.

So I've noticed closures in relation to this talk.

And we're going to kind split this up into two parts.

Relatively briefly, you go through the current approach to lip-learning therapy in the US, and spend some time looking at future directions as well.

I've said this in a lot of talks before.

It's really important to understand that the relationship between LDL cholesterol.

And cardiovascular risk is linear as your cholesterol goes down your risk goes down and as it keeps going down your risk goes down

And we've had a really hard time finding that bottom threshold as far as we can tell an ideal LDL is probably 30 to 50

And we used to say it was a hundred we used to say it was 70

It just keeps getting lower and lower a perfect LDL is probably 30 to 50

And so no matter where you are If your LDL goes down, your risk goes down.

That's exactly what we've seen in the statin trials.

As our statins have gotten more efficient, as they've gotten more potent, as people's LDLs have gone down further, their risk has gone down further.

And so the more aggressively you treat somebody's LDL, the more you lower the risk.

But when we talk to patients about taking a statin, we rarely hear, boy, I'm just not sure.

Instead we hear I'm concerned about safety I don't want any side effects which is understandable

That's should it be our goal as well and so recently we have some data looking at that

So the cholesterol treatment trialists have all the randomized data for statin therapy So they have the individual level data.

So this is the best kind of science when you're looking at these randomized trials And they simply published recently looking at the safety profile,

looking at musculoskeletal side effects on statin therapy for all the randomized trials that we have.

So this is a huge study, simply looking at one outcome of safety in terms of musculoskeletal side effects.

What they found is that for any muscle pain or weakness,

in 123,000 patients, so again, this is as much data as we have for pretty much anything.

The rate of actual reaction to the statin compared to placebo was about 0.5% higher.

So it was basically a 1 in 200 chance of actually reacting to the statin compared to a placebo medication.

So not zero by any means, but real.

of reacting to the stat,

and when observationally we see about 25% of people, about 1 in 4 have a concern about reacting to their statin.

In reality, by the trial data, it's closer to 1 in 200.

And if you look at the more intensive versus less intensive,

I think this is informative,

the people on high-intensity statins, compared to low-intensity statins, so some of the trials were not statin versus placebo.

They were a low-intensity statin versus high-intensity And in those trials,

the of reaction is a little bit higher on the high intensity statin, it's a 1.2%, so about 1 in 70.

And so this has been the theme that's been coming out of the literature in the last few years,

is that statins are very, very safe, but for the high intensity statins, there definitely is some risk.

People are more likely to react to the highest dose of a statin than the art of the lotos statins.

So do come with some risk.

And also importantly, if we look at the timing of reactions, if they split it up into early and late, this is really important here.

For the reactions within the first year, there's a definite increase here of basically a risk of about one in 100.

So about a 1% chance of reacting to this statin in that first year with serious musculoskeletal side effects.

If you go after year one, which some studies are up to seven, eight years, there's really no increase in risk.

whatever.

It's a zero percent chance.

And if this is going to happen, it should happen early on.

And I think this is important clinically because we have a lot of patients that come in.

They've been on a statin for four years and all of a sudden their knees started hurting.

I'm worried that this statin is now causing some knee issues or my shoulder pain or my back ache.

We can say with really good confidence,

if you've been on it for six months or more, the odds of reacting to it are almost zero.

We shouldn't really see any- And so now some of the recent research is focused on,

well, we have all these people that are reacting to statins.

It doesn't seem to be the statin by the trial data.

How do we figure that out?

How do we go about testing which people are reacting to statins and which people are not?

And if it's real or not.

And so this is the Samson trial.

This was published a couple years ago.

The original trial was in New England Journal just as a letter.

Then they published more detailed data in Jack.

This is a uniquely designed study where they took people with statin intolerance and put them in a trial for a year.

For four months, they were on a statin, a torvostatin, a 20 milligrams daily.

For another four months, they were on a pill that looked just like the torvostatin.

For four months,

they And so every month,

they switched on what they were on for that month,

and they kept track of a symptom score basically, how well they were feeling on and off the medication.

What they found is that when people were taking no treatment,

their symptom score here in the gray bar was an 8, which less than 10 is generally people are feeling good.

They're feeling generally well when they're less than 10.

The minute they started taking a pill.

It did not matter if it was the statin or the placebo, they felt twice as worse.

And so there's similar square went up to a 15 on the placebo and to a 16 on the statin.

And really this fits in the context of what we can understand from the science is that

the majority of people that have reactions to a statin,

we have pretty good science that it's not the statin, it's the concept of taking the statin, it's this no statin.

It's when you go to the medicine cabinet and you get out a supplement for your health, people tend to feel better.

If you get a drug that's associated with illness and toxicity, people tend to feel worse.

And we see this slight increase of the red bar here compared to the blue, because in a few people it actually is the statin.

And that's what makes this so hard, is that when somebody says, I think I might be reacting my statin, there's a chance they're right.

And we don't want to do any harm.

So we have to stop the medication.

But yet, we know in the majority of those situations, it's not the statin.

And so one of the things that we did recently here is try and take this concept of that trial that I showed you,

that Samson trial, a step further.

And so this is our decipher trial, which was funded by the foundation.

We ran this over the past few years here.

And so this was determining statin tolerance for a suicide statin.

That was decipher.

And what we did is we took people who had been intolerant.

of two prior statins so they had taken a couple of statins and had reactions both

times and this was primary or secondary prevention so it's kind of all-comers

and they could be on other lipid-luring therapy so maybe they were on

repatha or they're on zetia and doing fine and we double blinded them in a

n-of-one trial it's called meaning they're both the intervention and they're

the placebo

group so the patient gets a month of statin therapy and a month of placebo and a

month of statin therapy back and forth except they don't know what it's

in and I don't know what shorter it's in and so it was a six-month study so they

had three four-week courses of placebo so three of the months they were on a

statin sorry three months they're on placebo two four-week courses over suvis statin at 20 milligrams And again,

they don't know what your order is in, and week, sorry, each month, they would take a week off in between.

So that would get to six months total.

And if they were reacting to whatever they were taking, they should stop it.

So they stop it, wait a week, and start the next packet.

And we had about 24 people go through this study,

and what we found is that the mean pain score, whether you were on a statin or on a placebo.

So we had 129 weeks of a recubestatin, compared 176 weeks of placebo, and the pain score on average was exactly the same.

Their overall health actually trended towards being healthier when they were taking the statin.

And this was a P-value of 0.02, so I don't think that's real, I don't think you feel bad.

But the concept that you'd feel worse sure doesn't seem to the case based on the randomized data.

And then the whole point of the study was to say,

can we take this a step further,

and can we bring this data to the patient, and have them use it to make a decision about taking a statin?

And so what we had happen was that 24 people can send it for the trial, so there's a small little pilot.

Five of them what drew consent during the study, saying, I don't want to this trial anymore, it's too stressful, which is understandable.

Trying to assess these symptoms all the time, when you think you might react to your medication, definitely is stressful.

In those five that withdrew, none of them had any actual evidence of true statin intolerance.

One was lost to follow up, and the other 18 completed the full six month protocol.

Of those 18,

we had one where it sure seemed like when they're on the statin,

a week two and week three, their symptoms started to go up and on the placebo, it happen.

And one patient, it seemed like it was truly statin intolerant.

13 of them hadn't really no data where the numbers were just kind of all over the place.

There was no correlation with being on the statin and any other symptoms.

And then four had data which we couldn't quite know how to interpret.

They had one month that was bad and one month that was good, it kind of hard to tell what was what.

And we took that data to the patient and showed it to them and said, okay, here's your own data.

Are you now willing to try three months of unblindness?

it's that in therapy.

So now let's try this without the placebo design and to see if you can tolerate a statin.

And of the 14 that agreed to do that, so really we had 18 that finished the protocol.

14 said, yeah, based on what I'm seeing here, I think I'm willing to try the statin.

Of those 14, 12, tolerate it for a full three months.

And so we're able to get 75% of these people on a statin and tolerating it fine once they saw their own data.

You can tell a patient about 120,000 patient trial, right, with all this data and they're like, well, that's fine, but that's not me.

And so when you show them their own data saying this is how you felt on the placebo versus this,

how you felt on a statin, I think it's pretty compelling, it's pretty convincing.

So this potentially can be a method to facilitate statin, tolerance.

So we can take people who are intolerant from medication, have them go through the protocol, and get them on the medication.

And we have other options for lip-douring therapy, but still the foundation of lip-douring therapy for prevention is statin therapy.

And so potentially that could be of some use.

So we recently published this in Jack Advances as a research letter, and so now we're moving forward with a multi-center trial.

So we have several other institutions around the country.

And so we'll be starting that relatively soon, and I think it's going to be interesting see what we find.

So, obviously that's probably not going to be our bread and butter approach to statin intolerance,

because that's a bit complicated to do, and patients aren't super excited about participating in those trying trials sometimes.

Another alternative is simply not to use statin therapy, or to use less statin therapy.

And we have the improvement trial which was Zeddia, a Zeddia study published in 2014.

I think this is a large well-done randomized trial,

relatively straightforward design of a statin and a placebo in people post acute coronary syndrome versus a statin and zetamib, 10 milligrams daily.

And you see on the statin alone,

people got down to an LDL You think about our patients that come to clinic and their LDLs in the 60s say, you're doing great.

No changes is needed here.

That's right where we want to see it.

And on the zettia with the statin, they got down to an LDL of about 53.

So about a 15 point reduction, so not a huge reduction.

And yet over time, that was enough to result in a significant reduction in heart attack and stroke in cardiovascular events.

And even the low, the little bit of LDL lowering that zettia provided seemed to provide some benefit.

And then more recently,

they actually published kind of a secondary analysis looking at, well, can we do a better job of getting zettia to the right people?

And so this is that same trial analyzed in a little different way.

They basically took those outcomes and they analyzed them by the patient's baseline Timmy risk score.

So that's the score over here on the side.

And so these are all things that make patients higher risk.

And so you get worse.

And when they broke down the study,

half the trial,

so there was about a 17,000 patient trial,

half the trial had a score of zero or one, and that's this first group right here.

And in that group, there was really no benefit to taking this idea.

For that were low risk, Even if the LDL is a bit high, taking the zettia didn't have much benefit because they're low risk.

It's hard to prevent things that weren't going to happen in the first place.

And the zettia group really didn't benefit that much.

Conversely, if you look at this high risk group here, three or more, there's a 6% absolute

risk reduction with zettia, which is a huge number in terms of absolute risk reduction for lipid lowering therapy trials.

And almost all the benefit in that trial was just in that 25%

risk So again, the more we can allocate these things to the right people, the better we're going to do it.

The more we're going to reduce cardiovascular events.

And so in addition to Zeddia, we have the PCS-G9 inhibitor.

So I showed you the LDL reduction for Zeddia,

which in the trials from 70 down to about 55,

here in the PCS-G9 trials, in the placebo group, they're at about an LDL of 90.

So this is much more substantial LDL reduction.

This LDL a lot more efficiently than what Zeddia does.

And with that, in a short-term trial, we saw less cardiovascular events.

Again, it fits very much with that linear relationship.

The we can drive LDL down, the better people do.

And so some of the of this trial is that it's pretty short-term.

It'd be nice to see some longer-term data.

And so recently, the Fourier trial published longer-term data, their extension of the study.

So this is called Fourier, LA.

And the original trial was a two-year study, placebo versus PCSK9.

This study was the five-year data, and year two, when became unblinded, the PCSK9 was offered to everyone.

And so, anyone in the trial that wanted to keep in the trial could stay on it and be on the actual PCSK9.

There was no more placebo.

group.

And so what we see here, the LDL in the placebo group dropped to the LDL in the interventional group.

And so this is not five years of PCSK9 versus five years of placebo.

This is five years versus three years.

This is looking at starting the PCSK9 earlier in the course of disease.

And so it's not just a placebo controlled trial.

You're looking at just simply the starting earlier making And it definitely does.

That benefit that was seen in trial persisted and, in fact, expanded a little bit.

So you had a 15% reduction in cardiovascular events with earlier use of PCS9 therapy.

And the real theme of this is that the earlier we intervene, the better people do.

The longer you lower your LDL, the better people do.

And actually, they saw a reduction in cardiovascular death in this trial, about 13%.

And that's important because for most of the lipoloring therapy trials, we haven't seen that.

Most lipoloring therapy trials don't reduce cardiovascular death very well because there's deaths from heart failure, and deaths from arrhythmias, and deaths from aneurysms.

There's of things that lipoloring therapy doesn't affect,

and so typically it's been hard to reduce cardiovascular death in these lipoloring trials, and yet this one had it over five years.

And so if you remember any of the trials that we talked about today,

this is the one I'd like you to because this is kind of where the recent theme has been going in prevention for lipidorine therapy.

And so this is looking at using combination therapy versus simply high intensity statin therapy.

And so this trial was looking at ten-ever-subestatin and ten-of-zedia compared to 20-ever-subestatin.

And you think in clinic, we have that decision between 10 and 20.

We pretty lightly.

We just say, oh, either one you want to take is fine.

This looked at a high intensity statin versus combination therapy.

And the results were interesting.

So the red bar there is the people on combination therapy.

So if you take a low dose statin with zettia,

you're going to lower your LDL more than you So it's more effective at reducing LDL the combination is compared to the high intensity statin and if they looked at discontinuation for safety

They're much more likely to stay on the medication if we use the low dose combination approach

And so the high intensity statin definitely has more risk of side effects

There's more risk of musculoskeletal side effects and if you at that blood glucose change that we've seen the increase in diabetes in the statin trials

It's mainly at that high intensity dose.

The lower doses don't seem to do that near as much,

and so from a safety standpoint, it's a lot better to have a patient on ten or a suicide statin than it is on 40.

And if we use Zeddia with it, we're gonna have better numbers.

And so when they looked at outcomes, it was a non inferiority trial.

The red line is the combination group.

It was definitely non inferior, and there was a hint that it might be even better.

Because you're lowering LDL more,

you're going to And so if we have an intervention that's better and safer to me, that seems kind of like a no-brainer.

So the real shift has been we should be using more and more combination low dose statin therapy here moving forward.

I think for secondary prevention for our patients in the hospital with a heart attack or a stent, that probably should better.

We be using tenor-resubistatin and tenor-resubistatin, and going to work the best, and it's probably going to be the safest.

So this is our current approach of lipoid therapy, and is pretty simplistic, but I think it's pretty accurate.

Based on somebody's cardiovascular risk, we should have a really low threshold to put them on 10 milligrams of a rusubistatin.

If they have a risk factor,

if they have a family history,

if they have concern about the risk, if have a high calcium score, getting on that low-dose statin is a really good idea.

It's to the risk, and it seems to be quite safe.

We should have a relatively equally low threshold to add a zeta mibe to it again.

It's cheap.

It's effective It's very safe.

It really come with any risk of side effects And so I have a pretty low threshold to add that a zeta mibe to that low

And then we have the PCS canines for our people at higher risk who we don't get to our LDL with our initial approach.

And so there are a path on the probably once we save

for when we need them and they're very effective and insurance will prove most often right now.

And so to me, this is kind of the modern approach and the theme has been in the last decade or so.

We want your LDL for as low as possible, for as long as possible.

So the earlier we can treat it, the better people are gonna do.

Now thankfully we do have some other things coming down the pipeline here.

So we have some other options that can help kind of aid this approach.

And so now we have a called Enclisterin.

So Enclisterin is like for pathic, except it works at a more molecular level to inhibit PCSK9, and it has a durable effect.

So you do a dose, and then a dose at three months, and then from there on, it's every six months.

So it's an every six-month injection.

We're working on kind of transitioning it to be able clinic,

so a relatively safe way to give it, an way to give it, and it's quite effective.

It LDL again by about 50%.

That's similar to what we see with our path or a pryoin.

So having this option available for some of our patients that travel a or have a time with that every two-week dosing,

I think is potentially helpful.

We're going to start using this more and more, I think, as we go along.

We have Bempedoic Acid,

which is a medication It acts on the same pathway that statins act for a little bit further upstream compared to a statin and the unique thing about Bempedoch acid

That's a pro drug.

It's not actually an active drug when it's circulating your system It doesn't get turned into an active metabolite until it's in your liver

And so potentially that could lead to better safety where we see less musculoskeletal side effects because the Bempedoch acid really shouldn't cause

you Those because not active until it's in your liver We have a that reduces LDL by about 15%

And so, you know, that's similar to Zeddia, so relatively modest reduction, but yet now we have outcomes data supporting that it works as well.

And this is recently published in New England Journal in looking at cardiovascular outcomes in people who are statin intolerant.

Again, that's kind of the marking for this medication, that's who it would be good for.

And we see a 23% reduction in heart attack with use of this medication over 5%.

And so again, even small reductions in LDL have the potential to impact cardiovascular rates over time.

And then some of you may have participated in our Kevin Graham lecture a couple of years ago.

So this was Dr.

Katherus and who had started a company called Which was looking at genetic editing to reduce LDL and so now they have their first in human trials

They're publishing and the based on the dose they now can show that they can effectively reduce LDL by about 50 or 60%

And it's lifelong.

So it's a one-time infusion that goes to the liver and edits your PCSK9 gene Your PCSK9 protein then is defective and doesn't work

It's like a PCSK9 inhibitor and you're done for the rest of your life And so they have human trials ongoing,

they've been dosed,

the safety profile so far look really good,

and so we'll see what the outcomes show, but I wouldn't be surprised in four or five years if this is an option.

They're also working on therapies for lipoprotein A and for another ANGL,

PTL3, another one they're looking at where if we inhibited all three of those, your lipos are pretty much to perfect.

And so, in our future approach, I think we're going to be adding some Enclisterin, the every six month injection.

We have this Bempedoch acid, which for statin intolerant patients.

We have leg protein A, which I didn't touch on because Dr.

Martin, going to tell us about that.

And then potentially some genetic getting, which sounds scary, it sounds kind of frightening.

But far, the safety data look really great.

And so, yeah, we'll see where that goes.

So I think we'll save questions.

Dr.

Martin, we'll go next so we can do questions.

So Dr.

Bartignoni is our prevention fellow this year.

He's a fully trained cardiologist and PhD from Brazil and him and his wife and family came to the U.S.

a number of years ago.

He's been training in Montana during internal medicine and he's been participating with us in a research fellowship this past year.

He's working on several different projects and he recently was accepted into Texas Tech.

for cardiology fellowship so he'll be heading down there this summer and so

he's going to tell you about some of his work he's been doing on lipoprotein A.

That's all yours.

Can you guys hear me well?

All right.

Well I have no conflict of interest.

My objectives are to maybe we can understand a bit better the role of lipoprotein

Lil A and cardiovascular risk assessment and maybe discuss future treatments.

So little history in this 1960s, it was described Dr.

Carr from Oslo.

described that there was an antigenic variant of LDL, and already described the gene, lysogen phenotype frequency.

And 15 years later, they actually isolated the gene, and the protein that he was talking about, it very similar to plasminogen.

And now we kind of formulated, this is everywhere, anywhere you go, we talk about LPA, you're going to see this little structure here.

It is an LDL-like protein, but it is attached to, it's an LDL-like particle attached to this protein.

called apoA.

Now, as you can see, so apoA that looks like plasminogen,

let me see if there's a pointer here, looks like plasminogen, homology is very high, 90 plus percent.

There is this protease domain that does not And then there are these cringol repeats.

These are amino acid sequences that fold itself into like a pretzel looking protein.

And a cringol is a Danish pastry that looks like a pretzel.

discovered it gets to name it after their own pastries.

Plasminogen has a cringle repeat from 1 to 5.

ApoA skips 1, 2, 3, and has then cringle 5, and then a bunch of repetitions of cringle 4.

This is all important in the end.

when we're talking about testing for these things and the therapy.

So, cringle four then repeats itself to ten different cringles,

but cringle two here,

as you can see,

is the important one,

because the variance on the amount, the repetitions of cringle two is what's going to make take this protein very difficult to test.

And also has an important effect on atherogenesis.

So it is considered a risk factor for atherothermbotic disease and even aortic calcification.

It is genetically Well, it's co-dominant.

You from your mom and your dad, like the ABO system, and there is not much you can do.

Lifestyle modifications does not change the LPA, the expression of the protein, but it changes your risk factor.

And it is on chromosome 6 at the LPA gene.

Now, so the prevalence in the world depends on inheritance.

In Africa, it's about 30% of the population.

And then it traveled through Europe and Asia,

where Africans have the highest prevalence of elevated LP little late as,

if we, if we consider over 50 milligrams per deciliter 125 nanomoles per liter, then Southeast Asians, or sorry, South Asians, then Southeast Asians.

And the lowest are in Han Asians and Latin Americans, or actually I think the term was Hispanics mainly.

So in general, at least in America, 20% of the population will have an elevated al-Pilule as a risk factor.

Now how does this work?

It is an LDL-like particle, and the LDL that is attached to that protein has higher amounts of oxidized phospholipids.

So, it carries the LDL-like risks.

It atherosclerosis.

So it induces a small muscle cell proliferation and migration.

It also has, it penetrates through the endothelial wall, and then activates macrophages and increases inflammation.

But the protein itself,

the apoaprotein,

the plasminogen-like effect also increases thrombosis,

and also increases interluminal inflammation,

leukin-6 increase,

but it can penetrate to the interstitial cells of the aortic valve and induce calcification of those cells too, which is different from other lipids.

Now, the evidence-linking alpiline atherosclerosis has been all over the place.

In the beginning, there was a lot of difficulty making that link because of the way we measured alpiline.

In 2008, on the labs, kind of...

agreed on how to measure it, and we were able to make a more distinct link between lipoproteinoline and multiple types of atherosclerotic disease.

So we have long prospective studies, we have meta-analysis, we have Mendelian randomization studies with genome-wide association.

that have proven to link LPLA and ASCVD and also to aortic calcifications.

We have Mendelian randomization, even a Fourier trial help link that.

and schemic stroke is also a big one.

Now, this is our data here.

We published a meta-analysis that was just recently published at the European Journal of Preventive Cardiology,

the association between lipoproteinylate and coronary calcium scoring and progression.

Now, this is very interesting.

Well, we know it's a risk, but how much of a risk?

We have much more LDL circulating, LDL particles without the APOA attached to it.

So population-wise LDL carries a much higher risk,

but particle per particle,

This study also,

very recent study,

2024, has shown that lipoprotein little A carries six times more atherosinicity than one particle of LDL itself, whether it's due to the protein

itself or the increased oxidized phospholipid content.

And are many theories and hypotheses, but it does carry higher atherogenic effect.

Interesting things about population studies that we make 1,000 associations with everything.

And the higher the effect of levels, the lower the risk of type 2 diabetes.

Now, well, so you can say, well, it's protective.

And actually, it's not protective at all, but if you do have both, your your hazard ratio of having atherosclerosis is 1.9.

This study also, just recently it was published on the 18th.

It sent to me just a couple of days ago,

so it was quick to read and interpret what they meant,

but it's a pool cohort using mesa,

FHS and ARIC,

so pretty large,

20 plus years follow up,

showing that if you compared the lowest quartile at the highest quartile,

you can see an increment to each quartile there's an increment in risk,

and that risk was stronger in patients with diabetes than in patients without diabetes.

Pretty, very interesting findings.

Now, this is a borrowed.

So, at ACC, I was looking for a more objective.

Answer to give patients when you order LPLA and they're like, okay, this is a risk enhancer.

So what do I tell them?

And I hadn't seen this as incredible as things.

It's not new.

It's from 2021, but I saw this in ACC this year.

Now.

This is not a new graph.

This is from the Manelian randomization studies showing that the linear effect, like LDL, the the L-pilolate, the higher the risk.

Well, those, we can calculate the overall risk using the pooled cohort.

And we ordered L-pilolate, and like, all right, what now?

It went from 7.5 to what, 15?

What can we say?

So they came up with this equation where to every 15 animal of increment,

you can increase about 11% the risk on the overall pooled cohort risk.

An example is this patient's baseline risk is 10%.

He's intermediate and you dose alpylolane, it's 250 nanomol per liter.

That's a pretty high number.

Then, well, you divide that 250 by 50 and you elevate their risk 1.11 because it's to every 50, 11.

And then the new magical number that shows up is when you take into account the patient's output delay.

So from 10% went to 17.3.

In that way, you can help guide making decisions and how aggressive you're going to be on lipid lowering therapy or other things.

This is also not a new graph, but varying.

interesting.

So, on the, on this side here, you see that it is, we're looking at LDL, lowering, and on the right is LP low length.

Now, using genetic association, or genetic estimates, versus observational studies versus looking at what the statins and the PCSK9 studies got us.

We can say that if we want to reduce risk by about 22%, you have to reduce LDL by almost 40 milligrams per deciliter.

This is pretty well established.

Now, LP little a, we did

genetic, we did the Mendelian randomization studies,

observational studies show that you have to lower it in about 100 milligrams per deciliter to have the same 22%

reduction that you would with 40 milligrams reduction.

Uh, well, that's great, but nothing right now can reduce a hundred milligrams per deciliter, except if you're very high, very high levels and a PCSK9 might be there.

So that's why you see that the little dotted line here for trial is an estimated, it's a projection.

because most of the studies we have are phase 2 and based on genetic estimates.

Alright, so what can influence, non-genetic influences on alpilole?

Well, alpilole is mainly genetic, cleared by the kidneys, so if you have kidney disease, you will kind of accumulate it in your blood stream.

So the products can increase it three to five times, CKD increases, makes it larger to liver transplants, you donors, new LPA.

That's rare.

Thyroid disease though, hypothyroidism increases up to the low levels by a little bit, but increases.

And has minimal effect, but post hormone replacement therapy decreases by 25%.

Statins variable, some studies show that increase about 10% and PCSK9 can decrease it up to 30% if they're very high baseline.

So, what do we do?

So, you got the patient, he comes in, you calculate the risk, and you know the statins will elevate up a little late.

So, what do we tell them?

Well, like every single thing in preventive cardiology, lifestyle modifications is king.

You will,

with diet,

exercise, and having a healthy life the study is from the Norfolk EPIC study showing that in patients with low

LP or below median and above medium you can still have in all groups have a reduction in risk on unhealthy lifestyle.

And although, in those with higher LPL, they have a little bit higher risk, but still better than patients with normal LPL and unhealthy lifestyle.

So lifestyle is king.

Now, there's a question about PCSK9.

We can reduce an up to 30% if your LPL level are very high.

It is not yet out there.

There's studies going on.

We have to determine it.

There are questions about niacin.

Niacin reduces up to length about 30 percent.

But so far, nothing telling us that this is going to reduce mortality.

Aspirin's a big question mark, the world health.

A few post-hoc analysis of previous trials shown that the risk of bleeding in those with

elevated L-pilole is not the same as less than maybe due to the pro-thrombotic effect of L-pilole.

So less risk of bleeding and better preventive, so that's about it.

what to do with aspirin LPA.

The only FDA approved treatment is LPA of opharesis,

which is cumbersome but effective,

and it's on those cases that are very, very elevated, and then we're exploring the targeted therapies for phase 3 trials.

Before we there,

let me just kind of give you guys a little update on the,

so the,

on the,

this is,

this is a four-year study showing that alpilole on the left side here is showing that on,

only on a median, lower than median versus higher than median.

And then they kind of put it on less than 120, and I'm all per liter versus one over 120, which is considered high.

Showing that alpilole, evalucumab, did decrease risk compared to placebo in patients with low alpilole and high alpilole.

But alpilole did have an effect on both groups.

It increased risk in...

Therefore, it's not only a risk enhancer, but rather it can be considered a mediator here on all groups, not only an enhancer.

And this shows, like that dotted line we saw, this is a trial showing that the amount of LP little A to decrease.

about 20% in risk, in Fourier trial, was 16 animal per liter.

The other graph was in milligram per deciliter.

This is an animal per liter.

There is a whole new hour discussion on that.

We'll try to avoid it today.

And now, these are the opioidally targeted outcome trial.

Now, we have more than two drugs being tried.

I'll just speak about two because it kind of has a general, none of the results are out yet, anyways.

So the antisense oligonucleotide ESOs, so pelocarcin, and the trials LPA horizon, and then they're small interfering RNA, which is opossiren and ocean a trial.

Now, what did they do?

So, antisense oligonucleotide, you inject into the person, this antisense, it's a RNA strand that will

So, after the transcription of the messenger RNA, once that strand connects, it induces the RNA's to go and break down that messenger RNA.

You don't know how produce a protein.

And these are kind of short-lived,

so they're playing around with other carbohydrates and sugars attached to it so it lasts a bit longer, and they were very effective at it.

In small interfering RNA, it's bit different.

It's longer acting.

you inject this guide strand that interacts with the silencing complex.

And that kind of gets stuck in there.

And the cycle repeats itself, degrading mRNA for a prolonged period of time.

So it had, with one injection, a lot of.

So, these are phase two trials of ASO showing that you can reduce LPLA levels by 80% with

20 milligrams every week injections with minimal side effects, mainly injection site reactions.

And they said that over time,

this has maintained the 80% and you can have about 98% of patients having an LPLA less than 50 milligrams per deciliter.

So this is very effective.

Phase 2 trials are great.

we're going on phase three.

And are the small interfering RNA phase 2 results showing that with injections of every 24 weeks,

so very long-acting medications, you can have results mean prolonged mean percent changes of about a hundred percent decrease in baseline LP little light.

So these are the there these trials are going on throughout the world even here we have patients being selected here and they're a little bit

different from each other.

The LPA horizon is testing a little more patients in Ocean A and for a little longer,

but the LPA levels aren't as high as Ocean A, they're going for higher levels and a little shorter.

So who to test?

Now, when you are in clinic, especially primary care, and you have that very to talk about osteoporosis and pap smears.

And have to decide if you're going to go into the rabbit hole of checking further and what to tell the patient.

And then you have to remember, well, if there's a family history.

below 50, and if you had a high cholesterol, but then you did not have, you're not going to remember.

So, one after the other, the societies are coming down on to this, which I think is going to be very helpful.

Once in a lifetime, over 18 years of age, check it once.

Since it's stable, you don't check it when the...

but you check it in the stable in the outpatient setting, and you will have an idea of what the genetic outcomes there.

It's to be for L-p to L-l so universal screening.

This just came out April 2nd.

NLA had a long, lengthy, do do that, and you have to think about all this stuff.

But it's pretty clear.

Over 18, Check it.

We're good.

All right, so now what do we have here?

So this is a study we've been doing.

So we have data from 2004, 2023, so roughly 20 years, 419,000 patients, and 1.8% were tested for LPL.

Out of that,

419,000 patients from 40 to 79 years of age,

so we did not check the 18-year-olds,

median age 61, 52 percent female, 90 percent white, 61 percent this leap of and 11 percent with AS CBD.

Now.

That is the overall population of 40 to 79 of those 1.8%

had it checked 1.4% primary prevention setting and 4.9% and those with known established as CVD.

Now, this is interesting.

So, we had two measures that are changed in the labs.

So, if when we measured milligrams per the mass concentration blood, our median was 20

in those without AS CBD and the median was 27 and those per liter was also,

you know, this is considered very high levels of LPLA.

So 27%

of our population tested had elevated LPLA versus Whereas when we're looking at those studies,

the pool cohort studies are there show it was less than 20 percent And we think the world population in it was in America is about 20 percent.

So This is another this showing the proportion of elevated alpilinole and something happened here

in 2013 to that things changed well we had we had way to measure it and we changed the way to measure it.

And something happened again over here that changed again.

And we went to the third different type of essay that we're using.

Now we're measuring in particle number, nanomol per liter.

So, this is the amount proportion of elevated in percentages.

Now, this is the type of people we're testing.

In 2004, the majority of people tested were those with known established ASCVD.

And as time went by, something changed.

Now, we're going to a more primary prevention, low borderline risk patients are being tested.

patients with ASD.

So our outcomes are 30% of patients had elevated L-PLA in our cohort.

59 of them, when they checked again, vary 20%.

And we have very stable levels throughout the literature.

So something's up.

We've got to figure out.

why there's so much variance,

it could be unaccounted for for,

well, we checked it in very high risk, started a PCSK9 inhibitor, which known to decrease 20%, or they started on statins, or they stopped

statins.

So that's something to look at.

Or, it could have been also, we measured with an ethylometry in 2004, and then we measured it again in 2010 using immunotubimetric studies.

And there is an association of lipid-lory therapy and high alpilole.

7,618 patients were using lipid lowering therapy.

And can see in every single ASCVD group from low borderline intermediate high and established ASCVD,

LP-LA was associated with higher prescription of lipid lowering therapy.

Whether this is a cause or the effect, we don't know, this is a, cross-sectional in nature.

All just to end,

so my alpital leg talk is done here,

just to end a quick,

another result that we have from our studies here is showing that this is a STEMI study showing the

patients that showed up with STEMI to ER and we're looking, we have data from also 2003 all the to here.

The first decade of this study was already published by Dr.

Minima and now we're looking at the second decade of this study showing patients showed up with STEMI in the ER.

Were there any major changes in risk factors 10 years ago to now?

And were there any major changes in preventive medications from 10 years ago to now?

And difficult to see, I'm so sorry.

This graph here is showing risk factors, and this graph here is showing preventive medications.

Risk factor.

prevalence did not change much except for a slight increase in type 2 diabetes

compared to 10 years ago and the dotted lines here are secondary prevention and the lines are primary position.

We saw that there was a slight decrease in aspirin use from 10 years ago to now in secondary

Probably some confusion from the 2018 trials in aspirin misinterpreted the primary prevention aspirin versus this is secondary prevention.

That's my conclusion.

No one else's and And we saw that there was a slow,

a mild decrease in aspirin here, but there was an increase in ACE, ARB, and a little bit higher beta blocker use, but very mild.

So we can say that in 10 years, there hasn't been much change in preventive medications.

There hasn't been much change in traditional CVD risk.

except for slight increase in diabetes, and we have to reach people again a little bit earlier.

70% of the patients that showed up with a did not have established clinical ASCVDs, so they're unaware of.

before they had this technique.

All right.

We're happy to take any questions.

John?

Yes.

Thank you so much, both of you gentlemen, for the fantastic presentations.

We a couple virtual questions thus far.

The first comes from Dr.

Burke.

I think this came through during Dr.

Me to my York portion, but I could be wrong.

The question is, when and how do you treat triglycerides?

Yeah, that's been a little bit of a winding road.

You know, for people that have genetically They don't seem to increase cardiovascular risk.

They seem to be too big to actually penetrate vessel wall, and so they're not atherogenic.

And for the longest time, we're kind of ignoring triglycerides for the most part.

Now we have pretty good evidence that triglyceride-rich lipopropines can be atherogenic, especially in the context of metabolic oxygen.

You know,

Zaddia and Resuba Stat and lower triglycerides really well, and so that would be the main treatment for LDL is the same treatment for triglycerides.

We know that the new GLP1s for weight loss actually reduce triglycerides really well.

We do have a couple new medications that are being developed that can lower triglycerides substantially.

FQISA would be one of them, and so we've got a few patients we're using that in, and so we have plenty of options.

Quite often we get treated pretty effectively.

Thank you.

There's an additional question that comes from Dr.

Lester, I this is for Dr.

Martin Yoney.

The question is,

is in Clister and available now in the prevention clinic,

and I suppose this could be for both of you, and then the follow-up question is, is it or any other new medication subsidized?

Yeah, I'll take that one.

So there are occasional occasions we can get programs through the pharmaceutical companies or through other companies to subsidize them.

We can get them approved in certain situations.

And Clisterin has been interesting because it still doesn't have an trial, so we're kind of waiting on that.

But yet, we have really effective LDL loranesis.

quite safe.

The every six month dosing is potentially a advantage and so initially how we distribute the was a really good issue as we

were going through infusion centers.

Now that's kind of been shut down.

Now we're going to probably be giving it in the clinical setting or they can just ship it

to the clinic and give it to the patient right and click.

Nurse And so yeah, it's pretty variable from patient to patient.

I'm kind of vague on purpose because everyone seems to be different insurance wise But we've definitely had some insurance companies that will improve with glycerin,

but won't improve her patha And so it's pretty variable from person to person Yeah, come on.

Yeah, thanks really great talk guys One thing's I'm interested in I thought it was really remarkable when they did those three reversal trials that there was all this

reduction in plaque And now,

I missed part of your talk at the beginning,

but it seems like the theme is we can back off on the intensity of the stat,

and think specifically with Zoopa stat, and you were referring to it, and Zadia, get maybe even a better effect.

Outcomes seem to be similar, I guess.

And so do you think that in these patients, you may be seeing the same reversal if that's clinically important other than events?

Right, right.

So a good question.

So we had a lot of trials looking at high intensity statin compared to low intensity statin.

And the high intensity statin was better in terms of platform reduction in terms of outcome reduction, right?

And that seemed to be largely driven by LDL lowering, the LDL is what was most predictive of those things.

And if we can get to, you know, you get about 80% of the benefit of tenor of a in compared to 40.

And if you add zetia to that, you're going to go past that 40 of a in terms of LDL lowering.

And so you would assume the plaque reduction in the plaque volume.

because it really shouldn't be based on how much we lower LBL.

Do translate that to the atorvostatins?

Yeah, the data for atorvostatin or soussant are pretty similar, rousoussant may be just slightly better.

And then that safety debate definitely is better for that low dose roussantin.

40 and 80 of atorva have those similar kind of increases blood sugars and the higher musculoskeletal side.

Again, we're talking about high risk, we're talking about a% risk rate.

So not a high risk thing,

but in terms of stat and safety and what our patients want,

they seem to be very excited about getting a low dose approach compared to taking the high dose.

This is sort of the follow-up question and congratulations for all the publication you guys have done on this.

What is your view on ultra-low LDL in this world?

Let's say you have a study.

What would you want your LDL to be?

When you look at the really low LDL patients, what do you see in terms of outcome?

Yeah.

So, you know, there's a whole book called the cholesterol myth that it's all about how doctors are chasing cholesterol and we shouldn't be and that if we lower our cholesterol too much,

our body's going to fall apart and our brains are going to turn to bush and it's going to be really bad outcomes.

And a lot of that comes from a study out of Japan where the people with the lowest LDL with the least.

And that's, you can replicate that pretty easily.

In older populations, LDL is a marker for LT.

As you get end-stage liver disease or end-stage kidney disease, our malignancy LDL goes down pretty substantially.

And so if you inject it, then full of LDL, they wouldn't live longer, it's just a marker.

And you know,

the one of the ways PCS-900s were found is they found a couple people who had genetic edits in PCS-900 made it effective.

And so those families have LDLs of like five to ten.

They have basically got no LDL in their system and they seem to live long and they live well and they don't have any dementia.

They definitely don't have any heart disease.

A new more baby has an LDL 30.

Seems to be pretty happy.

And they built their whole brain on an LDL 30.

It like we've probably maintained ours on an LDL 30.

And so I think most preventative people would agree that 30 to 50 is probably enough.

ideal.

And so I think less than 50 is much what the European guidance is going to do.

It's pretty reasonable.

But again, how you get there matters, we don't spend too much.

And I think, you know, going to that, as soon as that is that, am I pretty quickly?

Is it a good idea?

If you get to 55 on that,

I don't think I would have a piece of skin inhibitor,

you know, and so the LDL goal is always get a little bit tricky in that setting.

It's about what you're using.

And so,

yeah, I think most preventive experts would say 30 to Also importantly, when you get, you know, the LDL is estimated based on that equation, right?

And that equation really breaks down when you get to that on the less than 40.

And so, a 5 could be a 20, could be pretty inaccurate.

And so, that's why less than 50 is probably just a better statement.

Thank you.

Yeah.

Just to wind back to primary prevention,

maybe you did a lute to this,

we have a lot of patients we see who just get calcium score because their second cousin collapsed or something.

And then they come in their 40s or maybe early 50s and we have to decide whether they have calcium score.

side whether you put these guys on lifelong statin or not for a combination of the sadia thing.

When you look at primer prevention by itself compared to the and the impact of therapy compared to secondary prevention,

do we see the same impact in these populations?

the casting score population is, I think, more heterogeneous risk.

They're not maybe as high risk as you might think.

Yeah, it's a good question.

It be really nice if 20 years ago they'd have done a randomized trial for calcium scores.

That would have been really nice.

We have a small one, but we don't really have any big data.

And so there's a lot of estimations By the data for people that have a counselor of 300 or more,

they have a risk equivalent to secondary prevention.

So that should be considered the same as a secondary prevention patient.

Whether or not the interventions work as well in that group, we don't quite know for sure.

Now, by the data, based on event rates with people's scores of zero,

it almost is impossible that in the primary prevention trials, the benefit was somehow different by calcium score.

It has to be in the people that have high calcium scores, because people with zero don't have any events.

And just by a number standpoint, the people that have elevated scores has to be where the benefit is.

And so, is it the same as secondary prevention?

Probably not, maybe a bit less.

But, for a suicide, we've got trials up to 30 years now.

And in 30 years, it doesn't seem to cause any harm.

And we're talking about at ACC,

they're looking at a trial, they're looking it as soon as then as an over-the-counter option for local health.

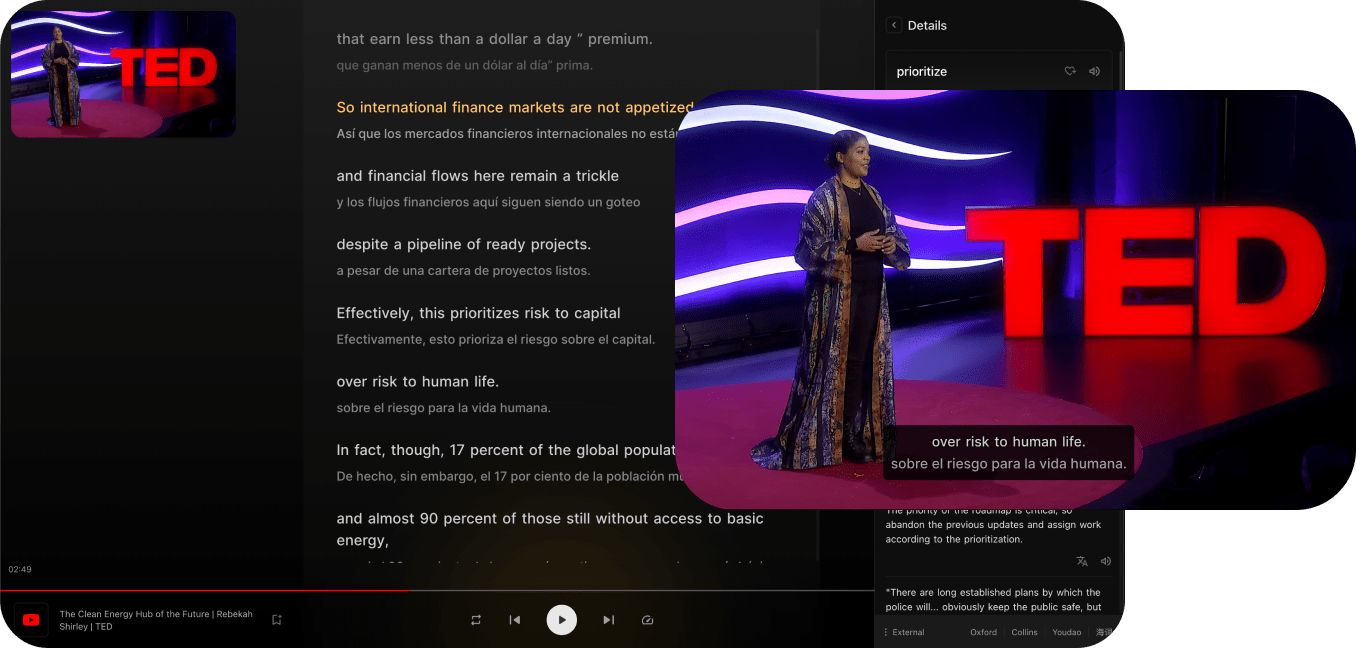

解锁更多功能

安装 Trancy 扩展,可以解锁更多功能,包括AI字幕、AI单词释义、AI语法分析、AI口语等

兼容主流视频平台

Trancy 不仅提供对 YouTube, Netflix, Udemy, Disney+, TED, edX, Kehan, Coursera 等平台的双语字幕支持,还能实现对普通网页的 AI 划词/划句翻译、全文沉浸翻译等功能,真正的语言学习全能助手。

支持全平台浏览器

Trancy 支持全平台使用,包括iOS Safari浏览器扩展

多种观影模式

支持剧场、阅读、混合等多种观影模式,全方位双语体验

多种练习模式

支持句子精听、口语测评、选择填空、默写等多种练习方式

AI 视频总结

使用 OpenAI 对视频总结,快速视频概要,掌握关键内容

AI 字幕

只需3-5分钟,即可生成 YouTube AI 字幕,精准且快速

AI 单词释义

轻点字幕中的单词,即可查询释义,并有AI释义赋能

AI 语法分析

对句子进行语法分析,快速理解句子含义,掌握难点语法

更多网页功能

Trancy 支持视频双语字幕同时,还可提供网页的单词翻译和全文翻译功能